Unit 5 - Perspectives and biases

| Site: | learn@inasp |

| Course: | Sample: Questioning as we learn - An introduction to critical thinking skills |

| Book: | Unit 5 - Perspectives and biases |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Friday, 22 November 2024, 6:06 AM |

Introduction and learning outcomes

This module focuses on perspective, i.e. our particular attitude towards or way of regarding something, and bias, i.e. our tendency to be subjective when we weigh a situation or judge something.

This module focuses on perspective, i.e. our particular attitude towards or way of regarding something, and bias, i.e. our tendency to be subjective when we weigh a situation or judge something.

Our background, our experiences, and our unconscious mind may lead us to perceive the same situation differently from others.

As critical thinkers, we would like to be as unbiased as possible, which is why, if we want to be fair in judging a situation, we should keep an open mind. We can do this by learning about as many other perspectives around one issue as possible before we make up our mind what to think and how to act.

Learning outcomes

This unit will ask you to:

- Discover the concepts of perspective and bias

- Identify diverse perspectives when interpreting information

- Identify several types of biases

- Reflect on perspectives and biases, your own and

others’

Banksy Pollard Street, East End of London (1)

Test your logical thinking skills

|

|

Practical activity |

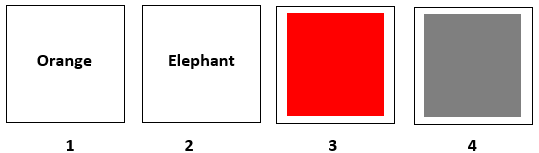

Here is a famous logic task for you to warm up with. A similar task was formulated in 1966 by the psychologist Peter Wason, who used it as part of an experiment on reasoning (2). Imagine that 4 cards are lying on the table in front of you. Every card has the name of a fruit or animal printed on one side and the colour red or grey on the other. As they appear in front of you, 2 cards show the name of a fruit or animal. The other 2 cards show a colour.

The 4 cards appear as illustrated below. Your task is to decide if the following rule is true:

If a card has the name of a fruit printed on one side, then it has the colour red on the other side.

Which card(s) do you need to turn over to find out whether the rule is true or false? Only turn over the minimum number of cards necessary to determine if the rule is true.

Tip: To organize your thinking about the correct answer, you may want to review your learning about conditional statements in Module 4 and draw a tree diagram for the logic task in this example.

Once you have thought your answer through, click on reveal to check your answers.

Perspectives

Perspective is defined as a particular attitude towards or way of regarding something, in other words, a point of view. As we look at something or someone, or watch a process or phenomenon unfold, we may see and interpret it differently from others because of where we stand and where we come from. Our usual way of doing things influences how we perceive new issues.

|

|

Exploratory activity |

Watch the 14 minute video below which explores issues affecting farmers’ adaptation strategies to cope with the effects of global climate change. Then answer the 2 questions below.

The compilation video was produced by farming communities across Sub-Saharan Africa. The programme that led to its production was implemented by InsightShare in association with 5 UK-based development agencies and numerous community-based organizations and local NGOs.

Questions:

1. What different perspectives or major concerns of the speakers can you identify? Which perspective(s) do you sympathize with the most, and why?2. What do people argue or advocate for? Which argument(s) stand out for you as the most convincing and why?

Video 'Participatory Video with Farmers - compilation' (3)

Once you have thought through your answers and made notes, click on "Reveal" to check your answers. Are your answers similar, or did you perceive the issues quite differently?

Bias

A bias is a genuine limitation in our thinking. It is not deliberate, but rather a flaw in judgement that arises from our tendency to be subjective, from errors of memory, from too much information, from limited understanding, from our need to decide or act quickly, etc.

Bias may lead to poor choices, as well as false beliefs and unfounded expectations.

Bias draw us to details that confirm our existing beliefs rather than looking for information that disprove our beliefs. It also makes us look for patterns even when being exposed to sparse unrelated data.

|

|

Energizer |

Can you spot an image?

Look at the picture below for 20 seconds. Can you spot any shapes, figures or objects?

Click on "Reveal" to check your answers.

Seeing patterns

In a very similar way to how your brain made sense of the clouds in the picture before, researchers may also see patterns in data collections that may only be random sequences of numbers or events. This tendency to recognize accumulations or clusters in random distributions is called a clustering illusion.

The picture below shows randomly generated points. However, you may see changing clusters of points appearing.

GIF 'RandomPoints' (4)

Clustering illusions have made their way into storytelling. Take the popular saying 'all (good) things come in threes', which is really a superstition feeding on our selective perception. For example, how many times have we perceived that we have experienced 3 good or bad things in a row, rather than 4 or 2 things in a row?

The reasonable explanation for it is that when we are looking for the (good) things to happen, we will find them, and with 3 being a ‘magical’ number in some cultures, we will look until we find 3 things in a row to confirm our belief in something.

Also, telling a story of 3 good things happening to us is much more interesting than telling the story of just 1 or 2 things. Such a story is much more likely to stick in our mind.

Quick brain exercise

|

|

Energizer |

|

Political map of South America (5) |

|---|

Let’s have another short brain energizer to keep you focused. Answer quickly the following questions. It’s not meant as a test of your knowledge about countries and population numbers, and you will learn more if you don't look the numbers up. So please just guess and jot down your answers with pen and paper.

Question 1

What’s the total population of Peru?

Select one answer option:

a) Higher than 30 million

b) Lower than 30 million

Question 2

Guess what the total population of Peru is. Estimate the number and jot it down, without researching it beforehand!

Question 3

Which continent is Peru in?

Select one answer option:

a) Africa

b) Europe

c) North America

d) South America

Question 4

What’s the total population of Colombia?

Select one answer option:

a) Higher than 30 million

b) Lower than 30 million

Question 5

Guess what the total population of Colombia is. Estimate the number and jot it down, without researching it beforehand!

Now look up the total population of Peru and Colombia! For example on this page. Which of your answers was most accurate?

Anchoring, confirmation, expectancy and cultural bias

In the previous exercise, which country population did you guess better? If for both countries your guess was around 30 million, the number which had been given to you as an anchor, then you have just followed another common human behavior called anchoring bias.

Anchoring bias often leads to poor decisions when estimating something such as the worth of an item you want to purchase.

For instance, let’s say the price tag says $1,000. You may be tempted to pay $800 for it, but think that $1,000 is too much. Now if you walk down the street and find another place where the same product goes for $800, you probably won’t spend too much time wondering if it is worth the money; you will buy it. However, you may be disappointed to find out that if you had started shopping from the other end of the street you may have found the same item going for $600. Except then you would have been tempted to think that it was only worth about $500 or so.

So anchoring bias occurs when individuals use the initially provided information to make subsequent judgments; the first piece of information offered (the anchor) affects us when making a decision. This tactic is often used in bargaining.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favour, and recall information in a way that confirms one's pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses, while giving disproportionately less consideration to alternative possibilities. Do you remember the Peter Wason experiment earlier, where people (and maybe you too) tended to pick cards that confirmed their hypothesis instead of disproving it?

Expectancy bias is linked to confirmation bias, and can be found in research, for example when researchers are drawn to details that confirm their existing beliefs, causing them to subconsciously influence the participants of an experiment. An extension of this is experimenter’s bias, which is is the tendency for experimenters to believe, certify, and publish data that agree with their expectations for the outcome of an experiment, and also to disbelieve, discard, or downgrade the corresponding weightings for data that appear to conflict with those expectations.

Cartoon from Crimes Against Hugh’s Manatees by Hugh D. Crawford (6)

Cultural bias refers to interpreting and judging phenomena by standards inherent to one's own culture. The phenomenon is sometimes considered a central problem to social and human sciences, such as psychology, anthropology, and sociology. Prejudice and stereotyping are examples of this type of bias.

Prejudice involves judging someone or a group of people before you meet them. It usually relies on stereotypes, which refers to judging a group of people different from you based on your own or others’ opinions formed as a result of limited encounters with people from that group.

It is important to remember that bias is mostly unconscious and includes thinking that we are less biased than others.

Whether we like it or not, bias influences all our decisions and behaviours. To limit its effect, we can keep an open mind, search for and consider diverse perspectives respectfully, and weigh them all carefully before making an important judgment or decision.

Learn more about bias: 2 activities

|

|

Optional activity 1 |

Listen to this 30 minute interview with Tom Gilovich, a professor of psychology at Cornell University. Keep in mind what we have covered so far and make notes on any biases mentioned.

Video 'Episode 8 − Extraordinary Claims: Uncut conversation with Tom Gilovich' (7)

Click on "Reveal" to check your answers.

|

|

Optional activity 2 |

Read the text below about conformity bias, which is our tendency to behave similarly to the others in a group, even if doing so goes against our own judgement.

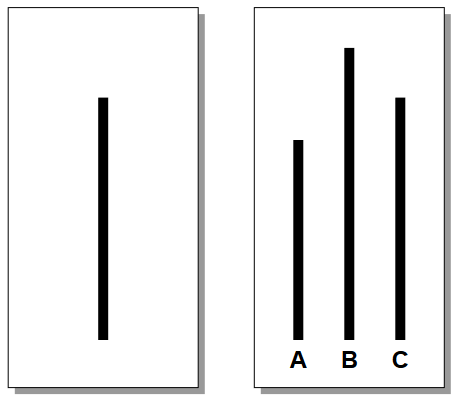

The Asch conformity experiments refer to a series of studies by Solomon Asch studying if and how individuals yielded to or defied a majority group and the effect of such influences on beliefs and opinions. Asch conducted his first conformity laboratory experiments at Swarthmore College, USA, in 1951, laying the foundation for his later conformity studies.

In this experiment, groups of 8 male college students participated in a simple perceptual task. In reality, all but one of the participants were actors - something the 1 test individual (the subject) did not know. The true focus of the study was about how the subject would react to the actors' behaviour. The actors knew the true aim of the experiment, but were introduced to the subject as other participants.

Each participant viewed a card with a line on it, followed by another with 3 lines labelled A, B, and C (see figure below).

One of these lines was the same as that on Card 1, and the other 2 lines were clearly longer or shorter. One would expect a near-100% correct response for such a simple task.

Each participant was then asked to say aloud which line matched the length of that on Card 1. Before the experiment, all actors were given specific instructions on how they should respond in each trial. They would always unanimously call the same line, but on some trials they would give the correct response and on others an incorrect response. The group was seated such that the subject always responded last.

Each subject completed 18 trials. On the first 2 trials (the control group), both the subject and the actors gave the obvious, correct answer. On the 3rd trial, the actors would all give the same wrong answer. This incorrect response occurred on all the remaining 15 trials. It was the subjects' behaviour on these 15 critical trials that formed the aim of the study: to test how many subjects would change their answer to conform to those of the 7 actors, despite the answer being wrong.

Asch expected that the majority of subjects would not conform to saying something clearly incorrect, but the results showed that as many as 75% conformed at least once, and 5% conformed every time. In the control group (the first 2 trials), with no pressure to conform to fellow participants, less than 1% of participants gave the wrong answer.

Subjects were interviewed and debriefed afterwards about the true purpose of the study. These post-test interviews shed valuable light on the study, both because they revealed subjects often were 'just going along' and because they revealed considerable individual differences.

Note that Asch used a biased sample in this experiment – all subjects were male, belonging to the same age group. In addition, one needs to keep in mind the political context at the time when the experiment was conducted. In the 1950s, the US was highly conservative, and so people holding left-wing views were being accused of being communist and put on trial. The suggestion is that people were reluctant to be seen as not conforming.

Critical reflections on perspective and bias

|

|

Exploratory activity |

Now reflect on what you've learned in this module about perspectives and biases.

Watch this 7 minute video where 2 members of a town council express their views about reducing the use of plastic bags in their community. While watching the video, reflect on the following questions and make notes:

- What do the speakers tell us about themselves? Knowing the speakers’ backgrounds can tell you a lot about which perspectives they are coming from. Personal background can also lead to individual biases.

- Which group of people do the speakers belong to or are important to them? The group they belong to may have a particular interest. Considering those allegiances will help understand what the person believes about the issue and what they assume is true.

- What arguments do the speakers express? Are there any premises which would need to be verified to be able to judge whether the arguments are strong or weak? Campaigners often present information so that it seems to favour them and their positions. People in a community may say things that are not necessarily true.

- Will anyone benefit or lose if the speakers’ arguments are accepted or rejected? Who gains if the information is taken at face value?

- Is the information complete? What is not spoken about? What else would people need to know?

- Has one of the speakers expressed a view or idea that is close to your own thinking? Do you think you could be biased when deciding how strong or weak the speakers’ argument is?

Video 'The Plastic Bag Debate' (8)

Click on "Reveal" to check your answers.

What have I learned?

|

|

Reflective activity |

Now reflect on your learning in this module so far, go over all your notes and then answer the 4 questions below:

- Are you now able to recognize different perspectives and identify some biases you or someone else may have in relation to an issue?

- How did you find the tasks in this module: too easy, too challenging, or just right? Which one was the most challenging?

- What are the 3 most important things you now know and did not know at the beginning of this module?

- How do you expect your new learning to impact your future response to information you read or hear?

| Write on the blog if you would like to share your thoughts with your fellow students. |

Comic from Crimes Against Hugh’s Manatees by Hugh D. Crawford (9)

References and further resources

Introduction and learning outcomes

1. Photo 'Banksy Pollard Street, East End of London' by Paolo Redwings, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banksy#/media/File:Banksy_Pollard_Street.jpg, licensed under CC BY 2.0, retrieved 16 March 2018Test your logical thinking skills

2. 'Wason selection task', https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wason_selection_task, accessed 12 January 2018Perspectives

3. Video: 'Participatory Video with Farmers - Compilation' by InsightShare (2013), licensed under Creative Commons Attribution licence (reuse allowed), retrieved 30 January 2018.Seeing patterns

4. GIF 'RandomPoints' by CaitlinJo (2013), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RandomPoints.gif, licensed under CC BY 3.0, retrieved 16 March 2018

Quick brain exercise

5. Image 'Political map of South America' by Yug (2010), this is a retouched picture, which means that it has been digitally altered from its original version, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:South_America-en.svg, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, retrieved 16 March 2018Anchoring, confirmation, expectancy and cultural bias

6. Comic from Crimes Against Hugh’s Manatees by Hugh D. Crawford, http://crimesagainsthughsmanatees.tumblr.com/image/158616111767, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0, retrieved 16 March 2018Learn more about bias

7. Video: 'Episode 8 − Extraordinary Claims: Uncut conversation with Tom Gilovich' by Think101 (2014), licensed under Creative Commons Attribution licence (reuse allowed), retrieved 30 January 2018Critical reflection on perspectives and biases

8. Video: 'The Plastic Bag Debate' by TheJHVoice (2012), licensed under Creative Commons Attribution licence (reuse allowed), retrieved 30 January 2018What have I learned?

9. Comic from Crimes Against Hugh’s Manatees by Hugh D. Crawford, http://crimesagainsthughsmanatees.tumblr.com/image/157466293247, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0, retrieved 16 March 2018Further resources

McLeod, S. A. (2008). 'Asch experiment', www.simplypsychology.org/asch-conformity.html, accessed 12 January 2018

Halpern, D. (2003). 'Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking', Fourth Edition, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, New Jersey.